Seeking Opportunities

North Side playgrounds were the start of athletic journeys for future prep stars

Posted: Wednesday, December 1, 2021 - 9:13 AM

While North Side playgrounds in Minneapolis were magnets of athletic opportunities for young people, too often, some were relegated to the sideline. Especially female athletes.

That didn’t sit well with Kathie Eiland-Madison in the late 1960s. So, she made a stand. Rather, a sit-in to protest.

She believed she was every bit as good as the boys at all sports, but at the time, females as athletes weren’t seen as much beyond the “tom-boy” tag. Eiland-Madison would show her disgust by not being selected to play in a pick-up game by sitting at midcourt. She’d refuse to move until someone took a chance on her or she had to be moved. Mind you, she was on the same court as neighborhood standouts Terry Lewis, Jimmy Jam and Jellybean Johnson. If those names sound familiar, you aren’t mistaken. All were bandmates in the Minneapolis-based group, The Time. Johnson, by the way, was the one typically in charge of lifting Eiland-Madison off the court and carrying her to the side.

“All I wanted was a chance,” Eiland-Madison said. “Those boys were phenomenal, but I thought, no, I knew, I could hang with them.”

At about the same time, Faith Johnson Patterson would watch from a window of her North Minneapolis home as neighbors, including rising prep star Ronnie Henderson, would play basketball in her backyard.

“I don’t know why they chose my hoop,” Johnson Patterson recalls. “I would watch them in amazement. I thought that it looked like a lot of fun. But I didn’t ask to get into their games. I’d walk down to either Willard Elementary or North Commons Park and try the game on my own.”

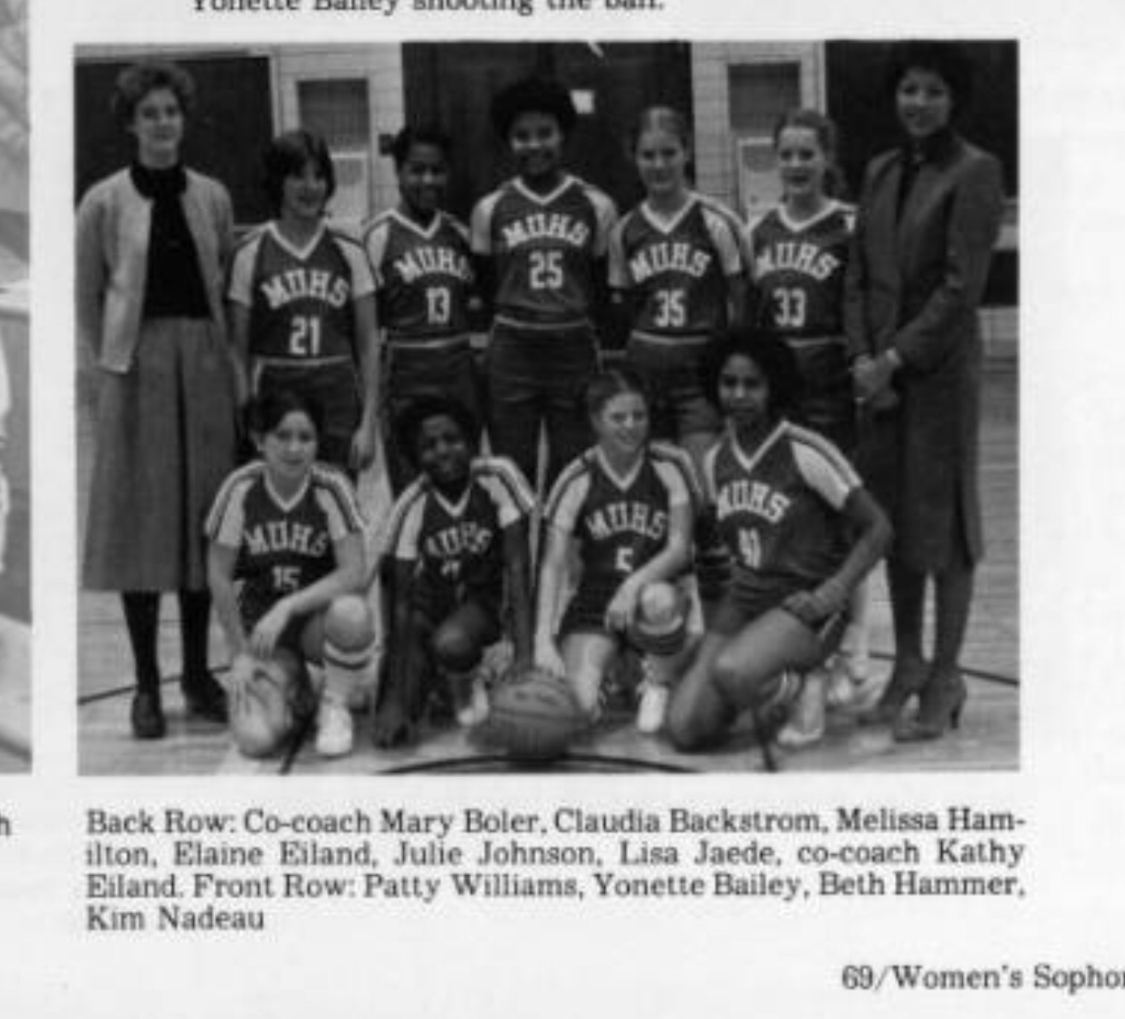

For both Eiland-Madison and Johnson Patterson, their journeys from the playgrounds of North Minneapolis led to Marshall-University High School in Dinkytown on the University of Minnesota campus. Their paths converged when Eiland-Madison was a senior and Johnson Patterson was an eighth-grader.

Eiland-Madison was a popular student-athlete that excelled in basketball, volleyball, track and field and cheerleading. She was a captain in those activities as well. Her athletic resume would include participating in the track and field state meet and being an all-state selection in leading Marshall-University to the first girls basketball state tournament in 1976. Eiland-Madison was also in the first group of Athena Award winners, an honor given to the top senior female student-athlete.

Johnson Patterson embraced the cultural diversity of Marshall-University and greatly enjoyed her high school experience. As for athletics, she didn’t think she had the basketball skills for the varsity level.

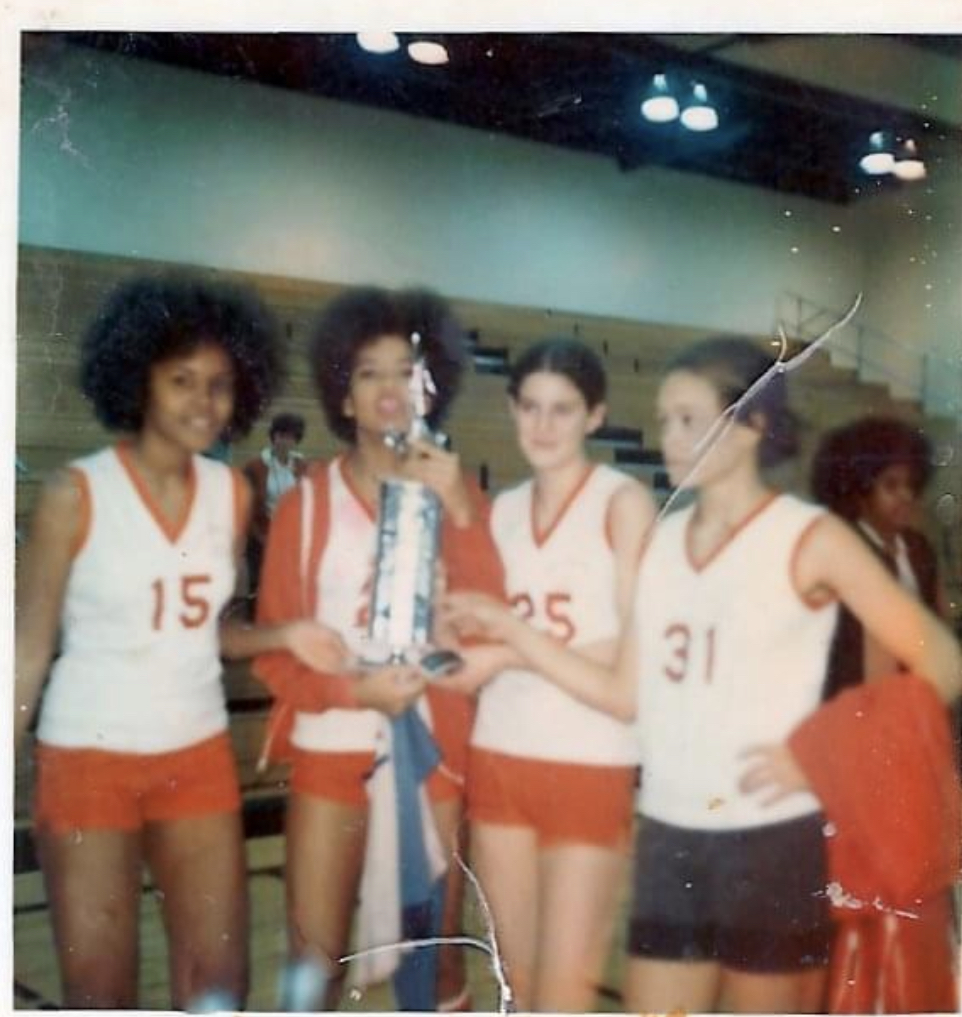

Kathie Eiland-Madison, second from left, pose with a coveted trophy.

“My mother wanted me to go to Marshall U,” Johnson Patterson said. “It wasn’t a private school, but it was a college prep school. I had an opportunity to get an excellent education. It was diverse. You saw different races and people got along. It was a great community school. It just felt comfortable. The seniors embraced the eighth-graders. Kathie and her friends allowed me to play with them. It didn’t matter what race you were or how good you were. It felt so good to be surrounded by people that genuinely cared about you.”

Eiland-Madison had to convince Johnson Patterson to try out for basketball at Marshall-University.

“She said she just liked playing for fun, but I kept at it,” Eiland-Madison said with a laugh.

The coaxing worked and helped pave the way for Marshall-University to qualify for the League’s first girls basketball state tournament in February, 1976. The Cardinals entered the tournament with a 19-0 record and finished fourth in Class A.

“To play in a state tournament was magical,” Johnson Patterson said.

“It was an opportunity to showcase the talent on our team and to meet other athletes that I have established lifelong connections,” Eiland-Madison said.

Eiland-Madison went on to play at the University of Minnesota. She is currently the Vice President of Human Resources-Diversity, Equity and Inclusion for Delta Dental of Minnesota.

Johnson Patterson, who would lead Marshal-University to another state tournament appearance in 1977, earned a scholarship to play at the University of Wisconsin. She moved on to become a Minnesota State High School League Hall of Famer as a legendary girls basketball coach. Johnson Patterson was the first African American woman to coach a League member school to a girls basketball state championship, and she’s done so a record eight times between titles at Minneapolis North and DeLaSalle. She currently coaches at Visitation High School.

As the Title IX legislation celebrates its 50th year, Connect caught up with Eiland-Madison and Johnson Patterson to share thoughts and reflections on their personal journeys through education and athletics.

Connect: As a female athlete growing up in North Minneapolis, what dreams did you have when few athletic opportunities existed?

Eiland-Madison: “My dream as a female athlete was to play in the NBA, however, that option was not available. And the WNBA did not exist at the time. My brother, David (a multi-sport standout at Minneapolis Roosevelt), said I would have played in the WNBA for sure. I was just too early.”

Johnson Patterson: “I just didn’t think that athletic opportunities existed beyond the park board level. I even stopped playing basketball for a while. You just didn’t see women’s basketball. I was exposed to college basketball accidently. We practiced at Peik Hall (on the University of Minnesota campus) and heard that the women’s basketball playoffs were in town. We watched Lucy Harris and Delta State playing at Williams Arena. One of the teams had a point guard that was 4-11. I was taller than her and felt I was every bit as good as her. That gave me confidence. It got me thinking about the possibilities.”

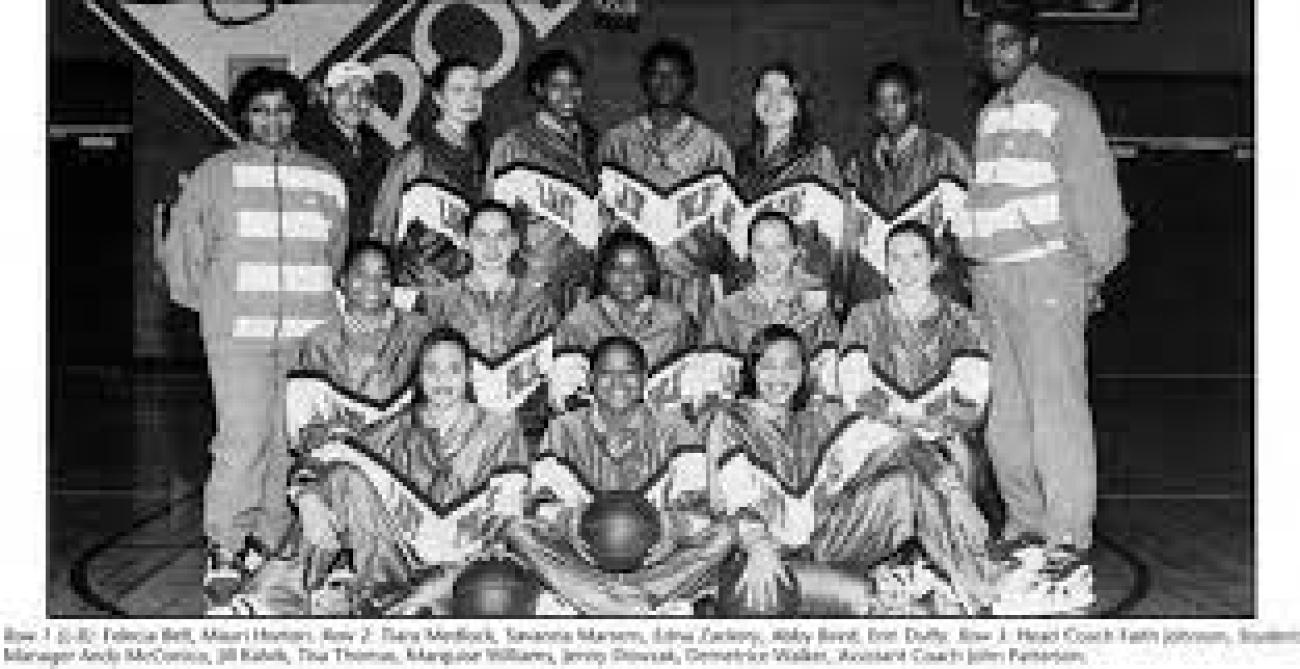

Faith Johnson Patterson celebrates a championship with the DeLaSalle girls basketball team.

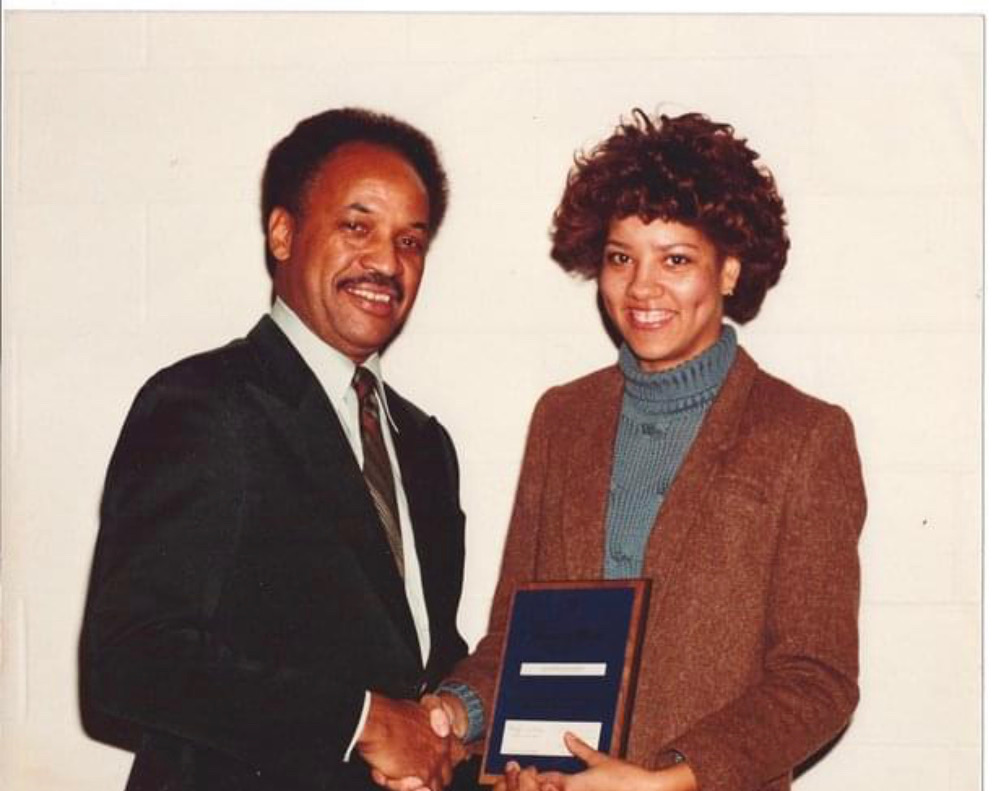

Kathie Eiland-Madison right, receives the Athena Award from Minneapolis Public Schools West Area Superintendent, Dr. Richard Green.

Connect: Who were your role models?

Eiland-Madison: “My role models growing up were both of my parents, Ray and Doris Eiland. They not only taught me to pursue my dreams, but they instilled in me the values of team, collaboration, fortitude and resiliency as they were both successful in the education and business sectors.”

Johnson Patterson: “Kathie Eiland and (St. Paul Central’s) Lisa Lissimore. Those two were everything I ever wanted to be. I was so inspired by both. They were the “wow” and the “it.” They were popular, beautiful and people wanted their autographs. Those two instantly were my role models, not only with how I wanted to play, but how I carried myself and who I wanted to be. It was like having big sisters. How they treated me, at my age, made an incredible impression.”

Connect: At the time, did you understand the significance of Title IX?

Eiland-Madison: “No, I did not understand the implication of Title IX during high school. As athletes who loved the sports, we were excited to play and compete, and recognized that sometimes that entailed playing with the boys. It wasn’t until college that I understood the true magnitude of inequity in sports for women that ranged from the financial budget impact, opportunities, exposure and fairness.

Johnson Patterson: “I did. (At Wisconsin) We would walk out of practice and see the guys would have a training table being catered to with full-course meals and other luxuries of the time. We had a meal plan at the dorm. They would fly to most of their games. The women’s team would take a bus or vans. I fully understand now. I was going through the conversion. I played with a men’s-sized basketball and never played with a three-point line.”

Connect: What were some of the challenges you faced in your participation in athletics?

Eiland-Madison: “There were several challenges relating to equity and fairness. As a young athlete playing basketball, my only option was to play with boys. Additionally, there were challenges in financial resources, equal playing time and recognition of our abilities to play at a high level.”

Johnson Patterson: “I was called a Tom Boy. I went from being teased and taunted to beating other guys to being selected first or second in pick-up game. I played basketball, but there wasn’t a women’s game that I was aware of to aspire to. I recall playing flag football and Terry Lewis was the coach. We were really good, but there was no women’s football at that time, either. I really enjoyed my high school experience so much. I didn’t experience any racial differences. Sports, that’s what did it for me. It made me feel like I belonged. Other female athletes ahead of me showed us the way.”

Faith Johnson Patterson, who has won eight state championships as a coach, talks strategy and motivates her team during a state tournament game.

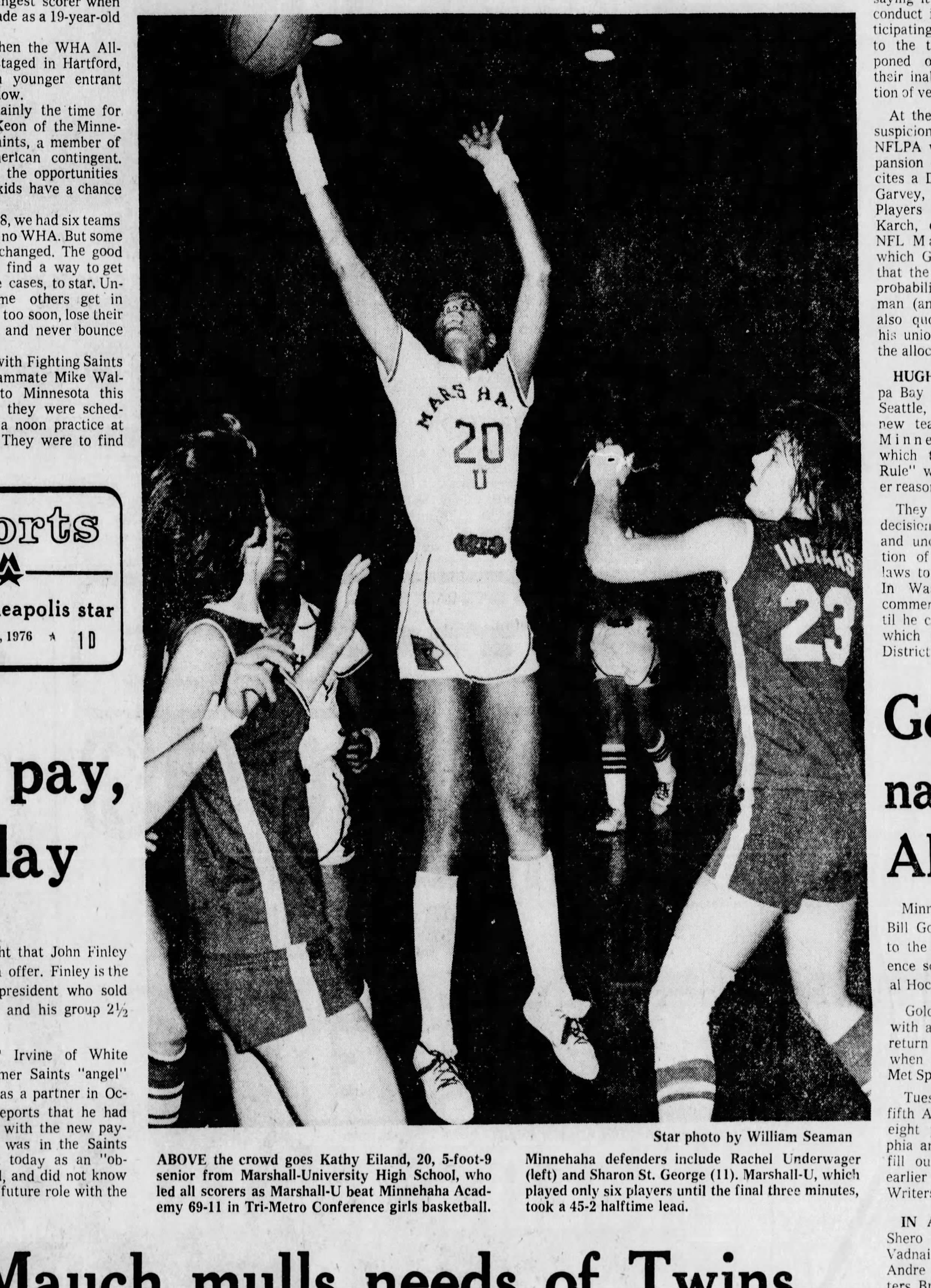

Kathie Eland Madison shows her shooting form during a Minneapolis City Conference game against Southwest.

Connect: What were some of the rewards?

Eiland-Madison: “A major reward was the opportunity to build lifelong friendships with my former teammates and competitors. Most of my teammates continue to keep in touch after our playing time. The interchangeable competencies of teamwork, collaboration, goal-setting, navigating through change, competition and strategy planning have been invaluable to me in my career as a leader in the Human Resources arena.

Johnson Patterson: “When I look back now, the unfortunate thing is that I accidently stumbled on a scholarship, not even knowing that they existed. There were other female athletes that were really good, and some even great, but didn’t get a chance to get recruited. There certainly wasn’t social media and recruiting websites back then. Meeting people has been a huge reward. Kathie and Lisa are some of my friends for life. My education through sports created confidence and gave me experiences that paved the way for the coach that I have become. I made sure that the people that played for me and the community we represented knew how valued they were. The fight for equity continues. When you grew up in an inner-city environment where there was gang violence and bad things happening, you want good things to happen for kids. Athletics, education and an opportunity to go to college are great rewards.”

Connect: As you reflect, what are some of your favorite memories that resulted in your participation in athletics?

Eiland-Madison: “My fondest memory was my senior year participating in the very first girls basketball state tournament in 1976. That is an opportunity that I will never forget. As for Title IX, it was a change to seek change, and I envision more systemic change. We made strides then and continue to do so now. We want to keep the momentum going.”

Johnson Patterson: “Being on that stage of a state tournament was one of the most incredible experiences of my life. Not (winning a championship) left a huge hole in me. Having that experience is what drove me to understand what that experience did for my life. It wasn’t just playing with great people and meeting extraordinary friends. It was just such an honor and incredible moment to be playing at that level. To get others to experience that state tournament is what drives me as a coach. Through my winning experiences, I have been able to be an advocate for girls and women’s sports for so many years. I have the opportunity to prepare young women to become great leaders. I want to be that role model for them.”